Sarah Needham

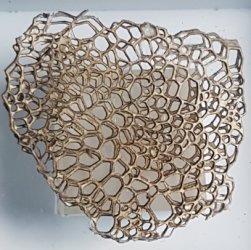

Painting, Other Media

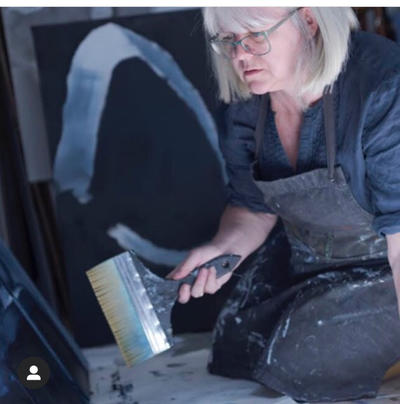

About Sarah

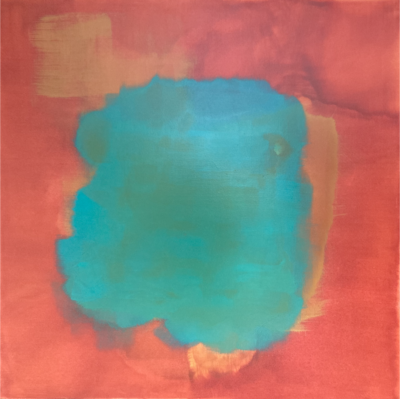

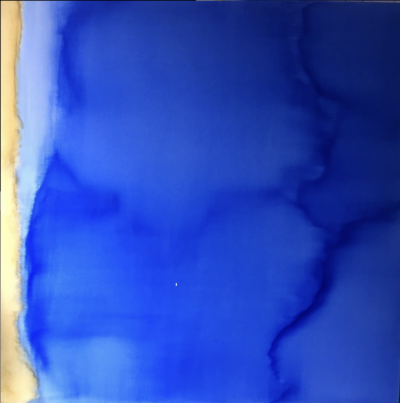

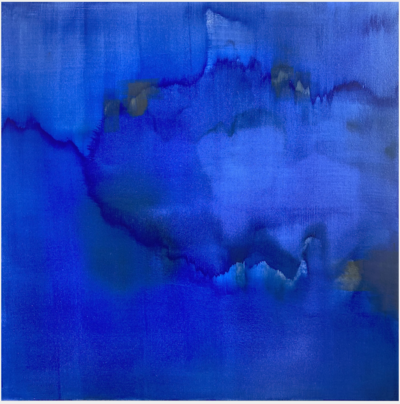

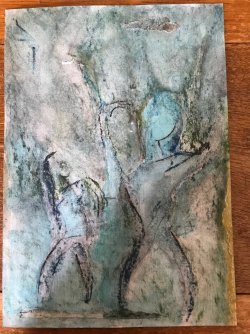

I start with the way in which pigments leave material colour across human history and geography leaving traces of our interactions. The projects chosen have resonance with the now. The form of the work is abstract spaces to fall into. I make oil paints by hand from the relevant pigments.

I make abstract paintings, spaces to fall into get a little lost and remember.

Email | sarahneedham@artfromlondonmarkets.com

Website | sarahneedhamartist.co.uk

Tel | 07964 913 056

My Work

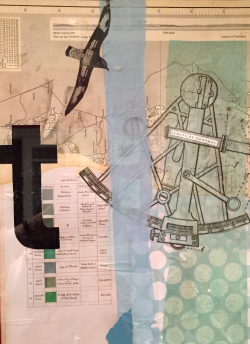

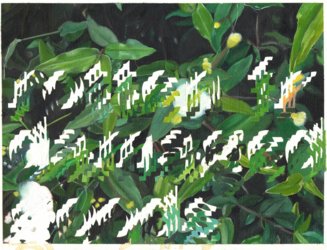

Each collection has a historic or geographic specificity: I have visited the 20,000-year-old cave paintings in Pech Merle and learned about the material traceability of ochres and that a prehistoric artist might have travelled long distances: Researching the British Library archive I found the historical spread of cobalt-based glass and glazes through archaeological finds, which illustrated the expanse of cultural exchange during classical and pre-classical times. Researching the pigments listed in the Bristol Library’s Presentiment Papers (1770Jan-June), I found evidence of transatlantic indigo just like St Katharine’s (see below), but also of madder, ochre and verdigris in a little pocket of peaceful trade between the European wars. I looked through The Admiralty papers at the National Archive, to find pigments in ships captured by privateers during the Anglo-Dutch Wars. Inspired by Turner’s Slave ship I have researched the pigments imported into St Katharine docks at the time of the abolitionist movement, and found indigo, a slave trade product, making it a colour of exploitation as well as beauty: I have looked at the evidence of Turner’s palette at the Tate, for the new pigments, at the turning point from a predominantly Colonial and alchemical to an industrial and scientifically based society. Always looking in these points of change for relevant echoes of our current flux.

The form my work takes is abstract spaces, spaces to fall into to get lost and to remember. I owe a debt to twentieth Century artists for the freedom to play in these colour fields, to Rothko and Frankenthaler, to Kandinsky, to Sonia Delaunay and breakthroughs with colour as substance. But also to the unnamed Church painters of the Middle ages for whom pigments had their own symbolism. Technically the medieval dislike of palette mixing, which was a question of material interference, echoed for me in retaining the integrity of a pigment for the story which it holds. And to the developments of oil painting by the Northern Renaissance artists and into the Southern Renaissance, and the technical traditions of glazing which allow me to layer and lends me an understanding of paint as a suspension of pigments which can be layered like strata.

My understanding and expression come through the exploration of these colour traces of our thought and history and the way in which the material holds its own story. That we must remember our human story, how we got here, how this society came into being and what the costs were is a given. There is a sense in which these colours hold more than the formal record, they hold nuance and space for connection, for potential and extant symbolism and for the stories never told.

Exhibitions

Exhibitions 2020-2022

- East Finchley Open Art Houses, June-July 2022

- The Other Art Fair, The Old Truman Brewery, Brick Lane E1, 17-20 March 2022

- Decorative Art nd Textiles Fair with Thomas Spencer Fine Art , Battersea, Jan 25-30 2022

- Winter Art and Antiques Fair, Olympia with Thomas Spencer Fine Art, Autumn 21

- The Decorative Art and Antiques Fair, Battersea with Thomas Spencer fine Art, Autumn 21

- Bath Antiques and Decorative Art Fair, with Thomas Spencer fine Art, 21

- The Other Art Fair, London, Autumn 21

- The Affordable Art Fair, Kahn Gallery Stand, London Summer 21

- Water|Land, Irving Contemporary, Oxford Summer 21

- Summer Exhibition, Silson Contemporary , Harrogate, Summer 21

- Solo Show at vintners Place, London May-Nov21

- Letters From A Strange Year Pop Up, Columbia Road, London April 21

- Autumn Show, Silson Contemporary Art Gallery, Harrogate, October-Jan 2020

- Winter Land, Nov- Dec Irving Contemporary, Oxford

- Artists Walk, Community Art Project North London, art in windows across North London, 14Nov-14Dec 20

- Highgate Contemporary Art on a postcard, Highgate contemporary online, Nov 20

Earlier 2020

- Summer Show, Gallery Artists, Silson Contemporary Art Gallery Summer show August-September 2020

- Unframed Highgate Contemporary Unframed online show May 2020

- V-Art.Show Online open studios April/May /June editions 2020

- Art on a Postcard with Highgate Contemporary Art in aid of Feed NHS sold out April 2020

- The Other Art Fair Online Studios, on Saatchi online April to October 2020

- Beyond Other Horizons: Contemporary paintings made in Britain and Romania, Iasi Palace of Culture, Iasi Romania. 1st- 31st March 2020. The exhibition will open on 3rd March 2020 with a British Council Symposium. Curated by Anna McNay, Peter Harrap and Florin Ungurianu closed early due to CV then extended to April

- Mid-Winter Show, Silson Contemporary Art Gallery, Harrogate, Yorkshire, Mid Jan-April 2020 Moved online

- Many of the planned shows and fairs were delayed postponed or as in the below cancelled due to Corona Virus

- Affordable Art Fair New York with Kahn Gallery, Spring: Cancelled 2020

- The Other Art fair London and New York cancelled 2020

Late 2019

- Makers and Craftsmen Project, curated interior by Bergman and Mar, Chiswick to winter 20

- Kahn Gallery at the Affordable Art Fair, Hamburg 14-17 November 2019

- Luminaire Arts Gallery, Beyond Abstracts, 7 Denbigh St London SW1V 2HF Nov-Dec 2019

Recent Competitions and Juried Shows

- 2019 Makers and Craftsmen, Curated by Bergman and Mar,

- 2018 The Black Swan Open selected by Johnny Messum, of Messums Wiltshire, Michael Eaves of Glastonbury Festival, Steve Burden Artist, Debbie Hilliyard of Hauser and Wirth, Sue Conrad Artist

- 2018 Long listed for the Secret Art Prize selected by gallerist Eleni Duke

- 2017 Creekside Open- selected by Jordan Baseman senior tutor at The Royal college of Art

Representation:

- Galleries

- Highgate Contemporary Art Gallery, Highgate High Street, London, N6

- The Kahn Gallery, London exhibits globally at The Affordable Art Fair

- Silson Contemporary Art Gallery, Harrogate Yorks

- Irving Contemporary Art, Oxford

- Online Sales Platforms with Art Agencies

- Saatchiart

- EPORTA

- Artists Agents

- Cramer and Bell, UK

- Luminaire Arts, UK

- Artiq, UK

- Artful, UK

- DAC Artist Agents , USA

- Publications:

- Beyond Other Horizons, Iasi Palace of Culture 2020

- Collections: Held in private collections in the UK, Switzerland, France, Australia, USA, the Middle East and Japan

- Graduated with a degree in Fine Art and Education from Hatfield Polytechnic 1989, a Masters Degree in Development Studies from South Bank University1994 and studied traditional Chinese Sumi-e ink painting under Prof Ding in Jiangxi China 2015-7

Other Artists

Lauri is a visual artist working in painting, drawing and illustration, with a special interest in the artistic process as a way of thinking.

View Profile

Cathy likes the challenge of working in watercolors as well as painting portraits in oils

View Profile

Ruth is a painter and sculptor whose work explores the transition of movement and energy between our inner & outer worlds

View Profile

Ann creates unique hand painted silks and fused glass pieces and jewellery, inspired by her love of colour. She also paints watercolours.

View Profile

David's paintings explore texture, colour and form creating an emotional landscape connecting with the viewer’s inner world.

View Profile